The Curtain 103: Listen, Look, Touch

Looping through media and the internet and our relations with the physical world

Welcome to The Curtain. This is Season 2, Episode 15 (issue 103). The Curtain is a newsletter about arts, algorithms, media, and consciousness. Season Two takes a special focus on the role of the internet. It’s written by me, Gus Cuddy.

Howdy friends —

Hope you’re having a good week.

Spring has finally made its full-fledged return here in NYC. 80 degree weather, muggy rain, a sense of sticky sighs and relief.

With vaccines circulating more and more, things have the sense of re-emergence here. An upswing into reality.

Feeling Good, Feeling Bad, and the Internet

As we re-emerge from a year spent dwelling in our apartments and inter-mingling via the super highways of the internet, I’m struck by how nice the outdoors feels. The awakening Spring, coupled with vaccine rollout, has brought with it at least some sense of renewal — amidst serious nationwide and global issues, in particular what’s happening in India. That creates a strange dissonance. Being vaccinated and knowing other people that are vaccinated all feels rather positive. There’s guilt over that, sure, but it’s also suspicion-raising: at least for those of us who were extra cautious over the year, getting drinks with friends in the pink-orange evening sun feels transgressive now, titillating and sexy. I still feel naughty having my mask down ever. But wow: it feels really good! Now I’m one of those people I had been so jealous of!

And jealous I’ve been — mainly through the internet’s favorite brand of jealousy, the Fear of Missing Out. That fear manifests mainly through social media, where the primary language has been a specific strain of FOMO for a while now. Whenever I open up Instagram, which I try not to do, I feel it’s a depression machine: I’m overwhelmed by other people doing things that look more fun, more attractive, more exciting than whatever it is I’m doing — that is, scrolling through Instagram, caught in downwards-spiraling webs. People look like they’re actually doing things and enjoying themselves during the pandemic? Blasphemy! In contrast, TikTok has acted like a fun-and-meme generating place, but the particularities of spelunking through its rigorous algorithm can lead to its own type of FOMO: gosh, everyone is funnier and more creative than me.

Netflix acts as an escapism hatch: a “lollygagging descent into the basest realms of content-consciousness”, as I’ve put it before, and a place where we’ve come to hide from FOMO for the past year. The content of Netflix is more curated and contained than the content of Social Media. Watching a Netflix hit, like Bridgerton or Ginny & Georgia, doesn’t generate the same feelings of FOMO necessarily, because watching them feels like like both an escape and engaging in some sort of twisted monoculture — even if only to be able to keep up with the conversation happening on somewhere like Twitter. (Of course, if you’re a creative orbiting the world of film/TV/theatre, watching things on Netflix can create a different kind of FOMO: why don’t I have a Netflix show too?)

But what is FOMO now? A fear of missing out on life, in some capacity. That there are things to be doing that we’re not doing. Ways to be happy that we’re not engaging in. The pandemic has accelerated these feelings, but there does seem to be an escape route: go outside. The “real world” and the digital world don’t live in diametric opposites, but they do live in contrast to one another, even as they shape each other.

Why can the physical world feel so free, in contrast to the digital world? Part of it can be tied to how media exist and have been transformed in the era of the internet — and how they stand opposed to live media. Media — on Social Media, Netflix, or elsewhere — exist in the spectrum of computers, and have been confined to the evolution track that their form puts them on.

Listen, Look, Touch

Recently many large companies have made announcements pertaining attempts to capitalize on the resurgence of audio as a major media form. Apple and Spotify both announced variations on supporting their own systems for paid subscription podcasts; meanwhile, Clubhouse’s audio-first popularity has meant every other platform attempting to replicate this feature in half-asssed ways — sort of like how Snapchat’s stories were quickly replicated in Instagram and then everywhere else. (Twitter Fleets and Spaces, anyone?)

This attempted capitalization of audio isn’t surprising. Venture capitalists have been writing about the under-monetization of podcasts for a while, with VC firm Andreessen Horowitz releasing a report in 2019 touting that “the biggest opportunities in the podcasting space lay in pivoting the business model from ads into some kind of direct payment.” In Tech terms, this means large corporations acting as Aggregators to compete to own the supply chain of the podcasting ecosystem, replacing a previously open system with walls, closed doors, and money. In 2021, even though many podcasts used paid subscriptions through services like Patreon — or through their own system — Apple and Spotify both refer to their new podcast moves as the “next chapter” and “new era”, respectively. Okay now!

Tech’s attraction to podcasts, though, doesn’t just stop with podcasts. That 2019 Andreessen Horowitz report claimed that “the bigger idea is actually ‘audio’, not specifically podcasting.” Audio, as in any recorded sound — what a vast, generic idea! An entire sense medium, waiting to be commodified. Spotify CEO Daniel Ek has made this idea of commandeering “audio” the entire manifesto of the company he leads, as he wrote in his Audio-First note in 2019.

Still, the very nature of how audio has evolved on the internet makes it resilient. Audio has become differentiated from video not just because of form and content, but because of data size. As I wrote about two weeks ago, the internet is all infrastructure, cables running through sewers around the world. As the internet has transformed, the technical capacity to transfer data has changed. The cheapest thing to transfer since the internet was invented was text: text is the original medium of the internet, spilling out from its original, central conception as an information superhighway. Text is trivial to transfer, and thus is, for the most part, open and free. After text came images. Images take up more data size than text, and are non-trivial to transfer, but as internet speeds improved the ease of transferring images improved as well, thus making them extremely common and open. Visual artists became able to share their work online, and images — coupled with text — became the basis for memes.

In the late 90s, as Napster rose to fame, transferring audio became more and more of a reality. Through its file-sharing-oriented introduction to the internet, then, audio became conceived of as a relatively open medium. It’s easy to share a music file with friends. Services like iTunes tried to curb piracy, but largely failed — until, ironically, Spotify came along. The cheapness of audio, based on its small file size, has had reverberations into how audio has developed on the internet. Audio has an informality to it that its openness helped define: it’s cheap and easy to record, cheap and easy to upload, and cheap and easy to transfer; unfortunately, in the context of music, this has led largely to a devaluing of the individual artist. (Record labels are also implicated in that devaluing; Taylor Swift’s re-recording of her albums is an example of the major artist trying to re-value the individual.) Podcasts became popular partially because of their hang-out, informal vibes. And now apps like Clubhouse ramp up the informality of audio to be entirely live, drop-in, and tossed off.

Video, contrary to audio, was a technical challenge to get up and going on the internet because of its large file size. Video inherently is heavier than text, image, and audio — it required much greater network bandwidth to be feasible. These technical requirements have coincided with how video has developed over the last 20+ years, which has been less open, and led to more vertical integration: big corporations like Netflix, Disney, Apple, Amazon, and HBO, to name a few, all produce their own video content. There has, of course, been the mass success of user-generated content on YouTube, and now TikTok — but those still came later in the development of the internet. And despite being more democratized, almost all video on the internet is still centralized through YouTube (or Vimeo). That’s because the infrastructure required to host and serve video is still immensely difficult to maintain — but a super corporation like Google has the resources to keep it up. The evolution of video has thus been much less open than the other mediums of the web.

So that’s text, image, audio, video — really the primary formats of the internet. They’re arranged in order of data size, which has affected how they’ve evolved as mediums. But what about the non-quantifiable, non-internet-ifiable mediums? I’m thinking here of things that don’t happen in internet space but in meatspace — with live theatre, concerts, dance, and art museums being perhaps the primary examples. What’s the data size of those? (It’s worth noting that many analog-world forms, like physical books or even takeout food, still are impacted by the ubiquity of the internet: they’re able to be bought online and delivered to you with relative ease.)

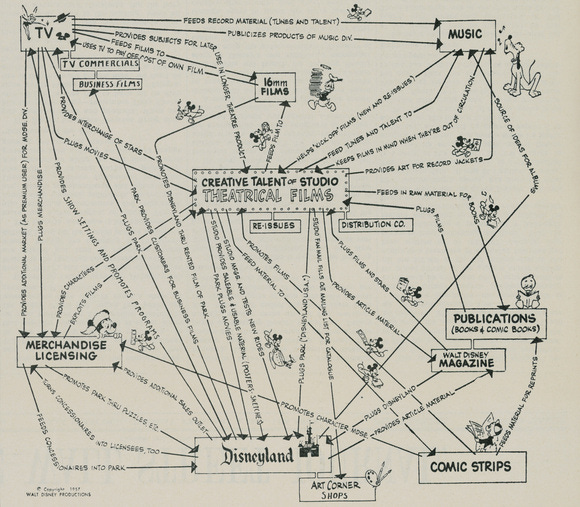

Sure, recordings and live streams and Zoom theater exist — and maybe they’re an adequate transposition of the live experience onto digital space in some cases — but here I’m talking about live experiences that can’t be quantified in that sense. Until technology has advanced to a point that that is actually quantifiable (VR? AR? something else?), some experiences are left to our physical bodies in a physical space — inherently scarce and ephemeral. Their file size doesn’t exist, and thus can’t be easily commodified by tech corporations. There are other ways to commodify the live experience though, as evidenced by Disney’s business model, where their content feeds into their theme parks, and vice versa. Walt Disney’s original flywheel drawing covers the ultimate capitalist media empire:

Disney’s version of sanitized liveness represents a path that live theatre, at least on Broadway, could be going down. But there are still experiences that can’t be plotted onto a flywheel. New theatrical experiences like Flako Jimenez’s “Taxilandia”, which is a live theatre piece that takes place inside a taxi, offer something that can’t be transferred through the infrastructure of the internet.

Which brings me back to FOMO, the internet, and the “real world”. Recently I’ve had to remind myself that there are people out there — actually, the overwhelming majority of the world — who aren’t on Twitter. Hell, there are actually people out there (many people!) who aren’t on social media at all. I know many literary writers, for instance, who don’t engage with social media in any capacity. Increasingly, I’m jealous of them!

What I’m jealous of, and what I’m driving at in this essay in a roundabout way, is the experience of being in, amidst, and of the world, rather than observing it through the refracted lenses of the internet. And as I see the streets of Brooklyn overflowing with people eating and drinking outdoors, I’m reminded that the live experience will continue to be primary in so many folks’ lives. The digital world still shapes the physical world in many ways, but it can’t take away the experience of being in live communion with others.

Increasingly, as we move forward out of this pandemic, I think the live experience will be heavily re-valued. So much of the past year, for many of us, has been filtered through the media of the internet, which is by necessity an abstraction of 1s and 0s. Much of art that participates in the internet has been shaped by the weird particularities of these 1s and 0s, and the relative ease of transferring them. But not all art can exist within these 1s and 0s. Whether that’s a good thing or a sign of irrelevance for live arts remains to be seen. But opening to the world again, seeing things anew, eating and drinking and breathing with other humans — let’s not underrate that.

Notes from the Week

Alisa Solomon in The Nation on How Covid Transformed US Theater

Scott Rudin has officially resigned from the Broadway League

David Gordon refuting the BS that, with Scott Rudin gone, we’re lacking in ‘visionary leaders’

RIP to Yahoo Answers, which is shutting down on May 4th. So many good memories of googling questions and ending up on this beautiful website.

Russian man ‘trapped’ on Chinese reality TV show finally voted out

“Don’t let him quit,” one viewer commented on a video of a dejected-looking Mr Ivanov performing a Russian rap.

“Sisters, vote for him! Let him 996!” another fan commented, using the Chinese slang for the gruelling work schedule that afflicts many young employees, especially in digital start-ups.

L.M. Sacasas, in an essay on information overload (emphasis my own):

In a talk Ivan Illich gave late in his life, he made the following observation: “Learned and leisurely hospitality is the only antidote to the stance of deadly cleverness that is acquired in the professional pursuit of objectively secured knowledge.” Then he added, “I remain certain that the quest for truth cannot thrive outside the nourishment of mutual trust flowering into a commitment to friendship.”

end note

That’s all for this week.

Season 2 of The Curtain will be wrapping up soon — I plan to write a few more issues and then re-assess for Season 3.

If you enjoy The Curtain, please share it with others!

You could also consider becoming a paying subscriber. I currently run on a patronage model: the benefits are the same (right now) for paying and free subscribers. Your support helps make this sustainable.

New reader? The Curtain is a weekly digital letter sent by Gus Cuddy. You can subscribe for free here, or browse the archives here.

You can reply directly to this email and I’ll receive it. So feel free to do that about anything. I love to hear back from people.

See you next week!

Gus